Pay-To-Win: How So-Called “Exploitative” Microtransactions Have Evolved

Microtransactions are a lucrative means of monetizing video games, and have become an attractive options for game developers to get more value from their games.

There are certain microtransaction models, however, that are considered by gaming community as “abusive and exploitative.” These models, labeled by gaming community as “pay-to-win”, are mostly despised for what is consider an unfair advantage that it gives to those players who can spend money to gain advantage.

Microtransaction models are not new, they have been around for years, not all of them are considered negative, players, sort of, recognize that some microtransactions are necessary for developers to earn financing necessary for updating and developing games. Many microtransactions changed over the years to maintain their ability to pull money from players while minimizing the negative impression, but this one particular type of microtransactions, pay-to-win, causes especially negative impressions and is hard to tolerate for many gamers. Let’s have a look at pay-to-win model – why does the label matter?

What is Pay To Win?

Pay-to-win (P2W) in video games is a colloquial term for the perception that a game’s microtransactions grant significant and unfair advantages to players that pay real-world cash for virtual items or services.

The key words here are “perception” and “fairness.” If a game’s microtransactions are perceived as P2W, it tends to gather negative feedback from consumers and often also from critics – making it difficult to gain new players in the long run.

Let’s say that you have an online competitive shooter that offers “golden bullets” that cost $4.99 a month and make 25% more damage compared to regular bullets, along with “golden vests” that also cost $4.99 and reduce damage by 25% when compared to regular vests. This direct exchange of cash for in-game advantages can be considered as pay-to-win.

The key here, however, is to spin these microtransactions in a way that reduces the perception that they are unfair – which is exactly what many of the recent microtransaction-heavy games are doing.

Offering Alternatives to Access Microtransaction Rewards

Money for time: this is the model that many microtransaction-heavy games have adopted, as evidenced by games like Clash of Clans, Clash Royale, Skyforge, World of Warcraft and Hearthstone.

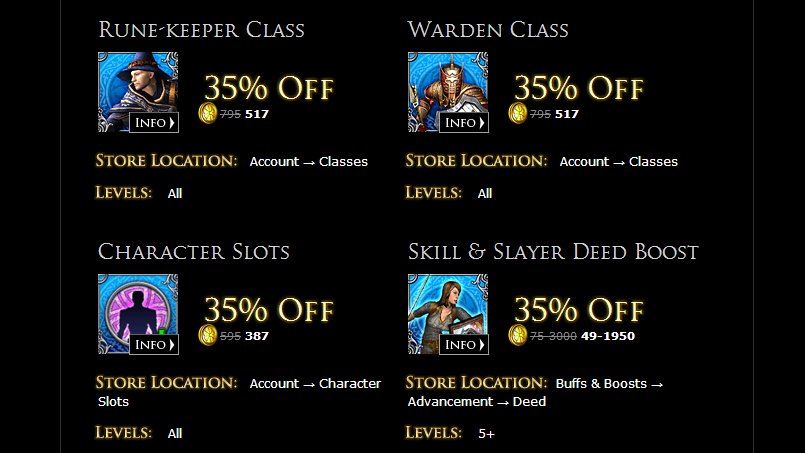

This works by making sure that all items that can be bought with real money can also be acquired by spending time on the game. For games like Clash of Clans and Clash Royale, players can let the timer on structures, upgrades, and units run out – or they can pay money to hasten the process. For games like Skyforge, World of Warcraft, and Hearthstone, players can spend a lot of hours playing the game in order to improve their character’s stats and obtain in-game resources – or they can pay money to boost the rate at which they gain experience and resources.

Opening up microtransaction bonuses in this manner significantly reduces the perception that the game is a pay-to-win. Nobody is forcing non-paying players to fork out money to enjoy the game, as they can get the same rewards as long as they are willing to put the time and effort into it.

Avoiding Situations That “Punish” Non-Paying Players

Another way to avoid the stigma of pay-to-win is to offer bonuses that confer bonuses to paying players without directly hampering the ability of non-paying players to enjoy the game.

In the above examples of “golden bullets” and “golden armor,” non-paying players will find themselves frustrated when they compete directly against those who bought the gold equipment. Paying players gain an advantage at the expense of non-paying players, who are put at a disadvantage, and this will definitely cause feelings of resentment.

This is an important factor when planning content for microtransactions. If non-paying players feel unfairly disadvantaged, especially after they have spent some time and effort progressing through the game, they likely to retaliate by living negative reviews.

The frustration is not very obvious however if players do not directly competing against each other in a game, for example in case of PayDay 2. The game is about players cooperating with each other to complete in-game objectives. Non-paying players can still do well and are not really frustrated by more superior armaments of their paying counterparts. The point is to make sure that the bonuses given to paying players do not directly conflict with the ability of non-paying players to enjoy the game.

Conclusion

These two factors – offering alternatives to access paid content, and ensuring that paid content does not directly harm non-paying players – are how games can avoid the perception of a game being pay-to-win while still maximizing the profit potential of microtransaction-heavy games.